Towards the end of 2011 2021 (in the depths of Covid…), I started

thinking about

adding a code of conduct to my open source software projects. Github

recommends adding one, somewhat similiar to how they recommend including a

software license.

In trying to pick a code of conduct (for my projects), it seems helpful to remember the “community”, as such, is often basically me, short (in length) is generally better, and just about anything can be weaponized by bad faith actors.

The Most Basic: Troll Banning

I suppose the most basic form of a code of conduct is just have a (written) policy to ban any trolls, or “Don’t be a jerk!”. It seems almost ridiculous that you would have to spell this out. But, I suppose as you start dealing with a wider array of people, it’s helpful to outline what behaviour isn’t appreciated (e.g. “Doing X makes you a jerk; don’t do it!”).

The Most Complex: Corporate Codes of Conduct

When searching Google for examples of codes of conduct, the corporate variety was by far the most common that came up; one could argue this is the “true” definition of the term. These tend to be very legalistic (being written by the legal department), very long (often hundreds of pages), and often very complex. But I don’t need all that: I’m don’t need to deal with travel reimbursements, I don’t need to deal with conflicts of interest, etc. I doubt anyone want to contribute a small fix to my software projects will read something that long, and I don’t want to spend the next three months (or three years!) writing something like this either.

The Most Common: The Contributor Code of Conduct

The Contributor Code of Conduct (aka the “Contributor Covenant”) is probably the most commonly used Code of Conduct for software projects and seems to have the largest mindshare; to some extent, it feels like the injunction to “add a code of conduct” is an injunction to bind yourself and your project by the Contributor Code of Conduct, whether you adopt that specific code or not.

It is among the three codes of conduct suggested by GitHub1, although the three of them seem similiar in nature. One of the three actually says the “primary goal of {COMMUNITY_NAME} is to be inclusive to the largest number of contributors, with the most varied and diverse backgrounds possible.”2…and I’m not sure that’s a useful goal for any (functional) group. For example, if you take any marketing, they will suggest having a “target audience” or an ideal customer to possition your project for. As a practical matter, if everyone is accepted, what is the common goal or purpose to hold the group together? As you deal with others, it’s fairly obvious that some people are more productive contributors, and some are more excited about the project; both things that I feel should be encouraged.

For me, the goal is to actually have a working piece of software, for me first of all. I don’t see how these codes of conduct help make that a reality.

The SQLite Option: The Benedictine Code

Presumably other (software/open source) codes of conduct have been developed (though none seem particularly popular), but one of the most interesting (to me) is the story of SQLite and their Code of Conduct adopted from the Benedictine Code. SQlite, for various corporate contracts, was asked to link to their project’s code of conduct, which at the time they lacked. Looking around, they decided to adopt the Benedictine Code, specifically Chapter 4. This Chapter is a list of 73 tools for good works and was originally written for the Benedictine monks ca. 530AD, and has been a foundation of their Order since. In reading through the list, it felt more like what I myself was looking for. In particular, it seems to focus almost entirely on the actions I want to see in the community.

There has been much critism leveled of it, mostly seeming to center on its religious nature. I don’t feel the Code itself is particularly religious, although it was written for a group of religious believers who are trying to better live their (shared) faith. Personally, it seems that some people mistake the mention of religion as implying that the text is a religious text, when it more often that the writers lived in a religious society (such as in this case). Perhaps the right response to these critisms is to request that other codes of conduct add religious identity and religious expression to their list of prohitied discrimination grounds (to mirror the current listing of “gender, gender identity, and gender expression”); often enough, religious people are asked to keep their faith out of sight as a condition of having it at all. Although the principals at SQLite do seem to be religious, they have also been clear that your (personal) religion will not bar you from participating in the project: in their introduction they explain that you are not required to believe, agree with, or even accept the Code to participate in their project.

Another complaint has been that it doesn’t lay out an enforcement mechanism. Except that it does, asking that those who have failed to live up to the ideals of the Code to be extended grace; for a first pass of many issues, this seems a reasonable response.

And the mention of chastity seems like a brillant way of heading off the sexual harassment and assult concerns that can be the most impactful for a community to protect against.

For Me

For my projects, I’ll be using a version of the Benedictine Code. It seems short enough that people may actually read it, it promotes the things I want to see in the community (rather than just being a list of horrible things people might do to each other), and its references to grace seem like a decent response to the misunderstanding most commonly encountered. Here’s the text:

Code of Conduct

Purpose

The Founder of this project has pledged to govern their interactions with each other and with the larger this project’s user community in accordance with the “instruments of good works” from chapter 4 of The Rule of St. Benedict (hereafter: “The Rule”). This code of ethics has proven its mettle in thousands of diverse communities for over 1,500 years, and has served as a baseline for many civil law codes since the time of Charlemagne.

Scope of Application

No one is required to follow The Rule, to know The Rule, or even to think that The Rule is a good idea. The Founder of this project believes that anyone who follows The Rule will live a happier and more productive life, but individuals are free to dispute or ignore that advice if they wish.

The Founder of this project and all current developers have pledged to follow the spirit of The Rule to the best of their ability. They view The Rule as their promise to all project users of how the developers are expected to behave. This is a one-way promise, or covenant. In other words, the developers are saying: “We will treat you this way regardless of how you treat us.”

The Rule

- First of all, love the Lord God with your whole heart, your whole soul, and your whole strength.

- Then, love your neighbor as yourself.

- Do not murder.

- Do not commit adultery.

- Do not steal.

- Do not covet.

- Do not bear false witness.

- Honor all people.

- Do not do to another what you would not have done to yourself.

- Deny oneself in order to follow Christ.

- Chastise the body.

- Do not become attached to pleasures.

- Love fasting.

- Relieve the poor.

- Clothe the naked.

- Visit the sick.

- Bury the dead.

- Be a help in times of trouble.

- Console the sorrowing.

- Be a stranger to the world’s ways.

- Prefer nothing more than the love of Christ.

- Do not give way to anger.

- Do not nurse a grudge.

- Do not entertain deceit in your heart.

- Do not give a false peace.

- Do not forsake charity.

- Do not swear, for fear of perjuring yourself.

- Utter only truth from heart and mouth.

- Do not return evil for evil.

- Do no wrong to anyone, and bear patiently wrongs done to yourself.

- Love your enemies.

- Do not curse those who curse you, but rather bless them.

- Bear persecution for justice’s sake.

- Be not proud.

- Be not addicted to wine.

- Be not a great eater.

- Be not drowsy.

- Be not lazy.

- Be not a grumbler.

- Be not a detractor.

- Put your hope in God.

- Attribute to God, and not to self, whatever good you see in yourself.

- Recognize always that evil is your own doing, and to impute it to yourself.

- Fear the Day of Judgment.

- Be in dread of hell.

- Desire eternal life with all the passion of the spirit.

- Keep death daily before your eyes.

- Keep constant guard over the actions of your life.

- Know for certain that God sees you everywhere.

- When wrongful thoughts come into your heart, dash them against Christ immediately.

- Disclose wrongful thoughts to your spiritual mentor.

- Guard your tongue against evil and depraved speech.

- Do not love much talking.

- Speak no useless words or words that move to laughter.

- Do not love much or boisterous laughter.

- Listen willingly to holy reading.

- Devote yourself frequently to prayer.

- Daily in your prayers, with tears and sighs, confess your past sins to God, and amend them for the future.

- Fulfill not the desires of the flesh; hate your own will.

- Obey in all things the commands of those whom God has placed in authority over you even though they (which God forbid) should act otherwise, mindful of the Lord’s precept, “Do what they say, but not what they do.”

- Do not wish to be called holy before one is holy; but first to be holy, that you may be truly so called.

- Fulfill God’s commandments daily in your deeds.

- Love chastity.

- Hate no one.

- Be not jealous, nor harbor envy.

- Do not love quarreling.

- Shun arrogance.

- Respect your seniors.

- Love your juniors.

- Pray for your enemies in the love of Christ.

- Make peace with your adversary before the sun sets.

- Never despair of God’s mercy.

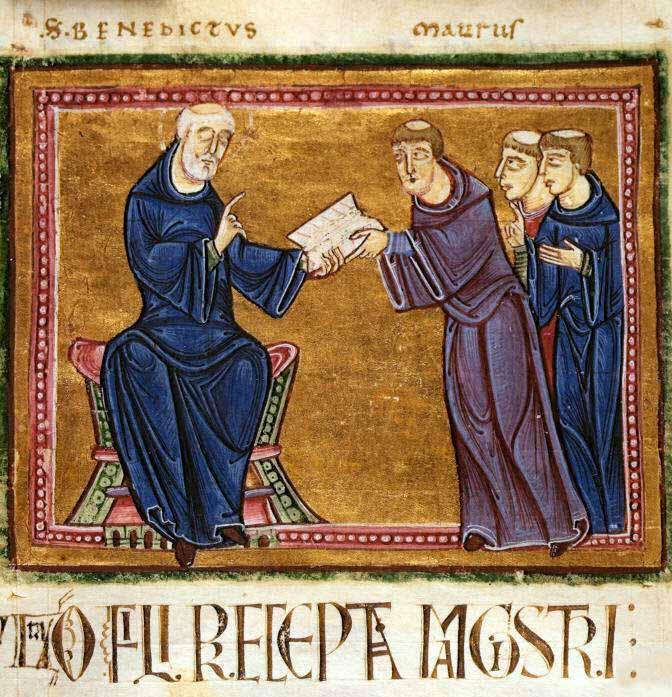

(The header image is “St. Benedict delivering his Rule to St. Maurus and other monks of his order”, from a manuscript from Monastery of St. Gilles in Nîmes, France, dated 1129. The image is copied from Wikipedia Commons )

-

the Contributor Covent, the Django Code of Conduct and the Citizen Code of Conduct are the three codes of conduct, from GitHub’s Open Source Guide. ↩

-

“Purpose” (the first section) of the Citizen Code of Conduct ↩

Comments

“Towards the end of 2011 (in the depths of Covid…)” — typo, or time travel? ;-)

Oh dear… maybe it was simulated time travel? At times, the madness of Covid did start to seem to have been going on for decade…

This should read “2021”, and I’ve updated the post. Thanks for catching that!