Abstract

Toronto has achieved a unique situation in North America; it is a major city that has maintained a dense core of population and employment with a well-functioning public transit system. This combination has made Toronto one of the most liveable cities on the continent. This is a result of years of deliberate decisions to integrate land-use and transportation planning, through policies such as zoning and parking controls, promoting public transportation and bicycle use, and limiting freeway construction.

A review of the various policies implanted, as well as their effects where appropriate, is presented, along with conclusions about what has brought Toronto success and how that can be repeated elsewhere.

Introduction

Toronto (see FIGURE 1), with a population of 2.5 million ([1]), is the capital of the province of Ontario and the largest city in Canada. Toronto also lies at the center of the “Golden Horseshoe”, an area which encircles the western end of Lake Ontario, which has a population of 8 million, or a quarter of the Canadian population ([2]). Toronto is a vibrant city with a rich history of public transportation, with some private streetcars operating as early as 1850 ([3]). The Toronto Transit Commission (TTC), established in 1954, operates the third busiest public transit system in North America (after New York City and Mexico City), carrying 2.5 million passengers a day([3]). Toronto operates three subway lines, and Light Rail Transit (LRT) lines, streetcars, and a fleet of buses ([3]). Toronto has been able to maintain a relatively dense core and impressive transit service over the years. A literature review was performed to determine some of the causes, particularly land use policies implemented, that have allowed Toronto to maintain such a strong public transit system. Conclusions and observations were also drawn on how the success of Toronto may be replicated elsewhere.

FIGURE 1 Toronto skyline ([4]).

The Planning Process

In short, land-use planning is the process where a municipality determines how land will be used within the region. In modern planning (post World War II), this process was fordist in nature, suggesting that land uses should be separated, and with a disregard for the past conventions such as mixed use developments and close integration of residential and employment, viewing these as out of touch with current desires and needs ([5]). The time period following World War II saw a great increase in factories, typically large, spread-out, single story structures, and it was typically expected that governments would act as enablers, providing the zoning required and housing (typically single family housing) nearby for the factory workers ([5]). Of this mentality, Newman and Kenwothy note:

“One of the features of 20th century modernism is functional isolation: architects, for example, believed that they could ‘make a statement’ with their buildings as though they did not relate to an urban context with a history or a local community.

“The same can be said about transport planning in its modernist phase which has been touched by a similar kind of arrogance. The civil engineer or economist who became a transport planner tended to see transport as isolated patterns of origins and destinations which were floating entities to be joined up by a straight line and be as fast moving as possible.” ([6], p. 1)

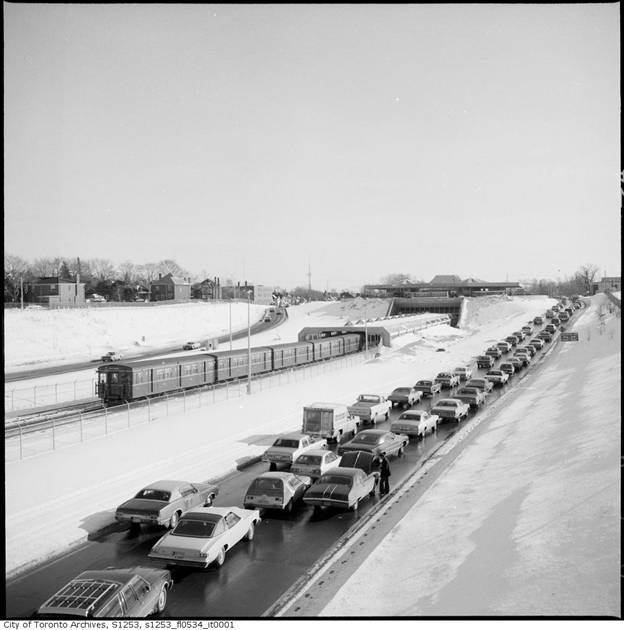

Toronto initially started down this course of fordist development, but a turning point came as the result of public opposition to and the eventually cancellation in 1971 of the Spadina Expressway ([7]). FIGURE 2 shows the corridor (roadway and subway line) along the corridor in 1978 upon the line’s opening.

FIGURE 2 Opening of the Spadina subway line, 1978 ([8])

A key figure in this movement was Jane Jacobs, who had recently moved to Toronto from Manhattan. Jacobs was active in opposing those projects which she saw as detrimental to a neighbourhood’s character, and eventually published The Death and Life of American Cities in 1961 which served to challenge much of the conventional wisdom of the time regarding land-use and city planning. Part of what set her book apart was that Jacobs did more than just criticize, but proposed an alternate model. In Death and Life, she makes four recommendations:

- A street or district must serve several primary functions,

- Blocks must be short,

- Buildings must vary in age, condition, use and rentals, and

- Populations must be dense ([9]).

Jacobs and her ideas remained influential in the planning process taking place in Toronto, and so rather than the expressway, a subway line was built. Today, many of the results of this change in attitude can be seen — within metropolitan Toronto, 35 percent of peak trips are on public transit and 65 percent of trips to the central area are handled by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) and GO Transit (a regional rail commuter system operated by the province of Ontario). Indeed, no major roads have been built within the central areas since the Gardiner Expressway and the Don Valley Parkway were linked in 1966. Stewart and Pringle further note that over the last 30 years, automobile traffic volumes have remained stable despite a near doubling of office space within the central area ([10]).

Historical City Design

To understand how the urban form within Toronto has been shaped over the last decades, it will be useful to review the history and evolution of the layout of a city. Newman and Kenworthy make a note of three predominate forms: the traditional walking city, a city with tram-based suburbs, and the automobile based city form. What ties the three together is that, in general, people do not like to travel more than 30 minutes to their urban destination ([6]).

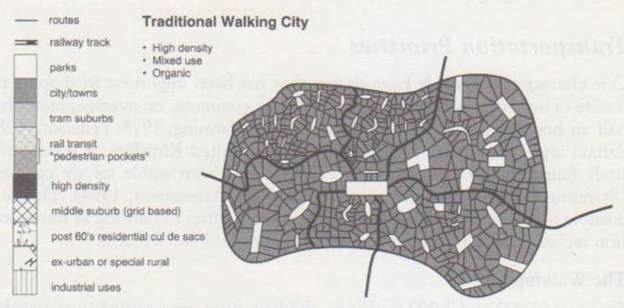

The Traditional Walking City

The traditional walking city was the first city form to emerge, as much as 10,000 years ago. The primary mode of transportation was by foot, and so as such, cities were rarely more than 5 km across. Densities were often high — as much as 100 to 200 people per hectare ([6]). FIGURE 3 shows a typical layout of a traditional walking city.

FIGURE 3 Traditional Walking City ([11]).

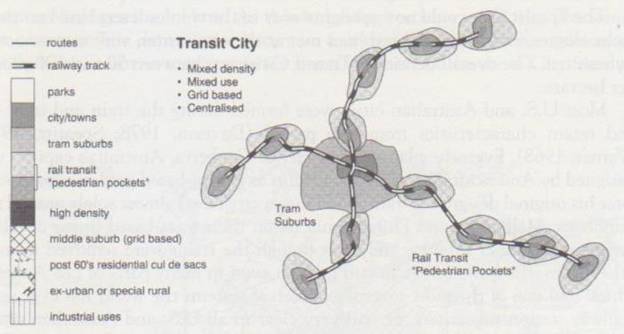

Tram-Based Suburbs

In the early 19th century, the invention and implementation of rail based urban travel, in such forms as trams and streetcars, allowed for the development of more remote ‘suburbs.’ Activities would typically concentrate at railway stations or along tram lines. Most systems were radial in nature and so the central city remained the hub of economic activity. This allowed the city to spread to 20-30 km with lower densities (50-100 people per hectare) ([6]). FIGURE 4 shows a typical layout for a city that has developed into tram based suburbs.

FIGURE 4 Tram Based Suburbs ([11]).

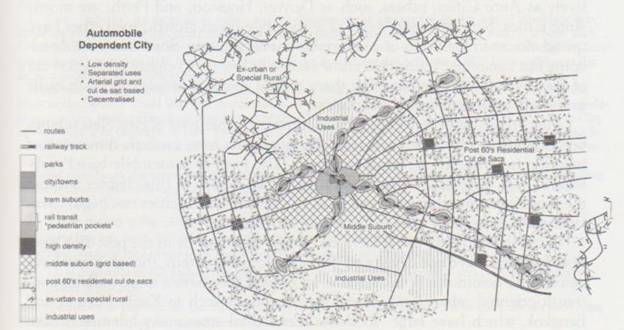

Automobile Based Suburbs

Although automobile based suburbs first came into existence before World War II, their development was greatly magnified afterwards. With the private automobile, the space between the radial arms of the rail network were filled in with low density, automobile based activities, and then the development continued outward, as far as 50 km from the city center. Density was also low, typically 10-20 people per hectare ([6]). FIGURE 5 shows the typical layout of a city that has grown from a tram based suburbs to automobile based suburbs.

FIGURE 5 Automobile Based Suburbs (11).

Toronto’s Application

Toronto initially developed based on the walking city model and then progressed to a city with tram-based suburbs. What makes Toronto unique among North American cities is that it has maintained much of the character of the tram-based suburbs and has continued to grow in this fashion ([6]).

Toronto has employed four strategies in particular to this end. The first was a suburban density formula seeking to confine high density developments (particularly high-rise apartments which were constructed in great numbers during the 1950’s to 1970’s) to arterials, on the logic that these arterials provided the best access for these residents to major bus routes with low headways already serving these corridors. The second strategy was to align density with transportation. Indeed, it was accepted that with high density redevelopment along proposed subway lines, this new development could provide enough ridership alone to justify the construction of the line in question. The third and fourth strategies, developed later, were those of nodal development, and “main street” corridors. Nodal development was suggested in part to relieve the strangling transportation congestion that had developed as a result of employment concentration in downtown Toronto, and create nodes further afield that would provide a concentration of employment, housing and commercial activities to be amenable to good public transit service. The fourth development technique, that of “main streets” corridors, sought to redevelop corridors of single story commercial development with buildings of three to six stories in height with commercial at the street level with residential above ([12]).

These various techniques have had limited success, as they have run into a number of “real world” conditions such as a drop off of high-rise construction in the 1970’s to provide high density redevelopment, concerns of Not In My BackYard (NIMBY) in reaction to redevelopment programs, and a stagnation of public transportation funding for many years. However, North York Center has developed along the node ideal, achieving over 20 percent public transportation share, while Scarborough Towne Centre approaches that level. The ‘main street’ model, while yet to be well received in the inner suburb areas, has been applied well in principal within the center of Toronto and inner city areas ([12]).

Toronto by the Statistics

Toronto, because of the choices it has made since World War II, has developed into a much different city than the typical American city. Kenworthy and Laube performed several comparisons, based on 1990 data, and found that Toronto, compared to the average ‘American’ city, has about 3 times the density (41 people per hectare, versus 14 in the United States), a third the road supply per capita, significantly less parking downtown (176 parking spaces per 1000 jobs within the Central Business District (CBD) versus 462), and nearly four times the transit service (106 km of service per capita per year versus 28) ([13]). The numbers show what can be confirmed through observations — while most American cities have developed around their freeway systems, Toronto has forgone freeway-based development in favour of an approach that has seen public transit be successful within the greater Toronto region.

Transportation Policy in Toronto

Although not formalized until 1976, many policies promoting public transit, or at least discouraging Single Occupancy Vehicles (SOV’s) within Toronto had been introduced in the two decades previous. Stewart and Pringle note that not many official Traffic Demand Management (TDM) measures have been introduced, in part because of the lack of a perceived problem, such as particularly bad traffic congestion, poor air quality, or a fossil fuel shortage ([9]). Toronto has sought to maintain and increase the housing supply within the central area of the city, as well as maintain employment concentration. Thus, many people can live very close to work, reducing the number of trips needed and their length. Indeed, it has been noted by Frank and Pivo that increased work density does more to reduce trip length than increased housing density ([14]). One of the landmark studies on housing in the central area of Toronto is Nowlan and Stewart in which they found that for every 100 additional dwelling units in the central area of Toronto, there has been a reduction of 120 inbound trips during the morning rush hour ([15]). Based on this, Stewart and Pringle postulate that if a housing unit were added for each additional 30 m2 of office space, there would be no net change in inbound peak-period trips ([9]).

Zoning and parking requirement laws were also revised, and the old requirement of one parking spot per 93 m2 of office area was repealed and replaced with a new requirement of one space per 300 m2 of floor space and a maximum of one space per 135 m2 of floor space ([9]). When the Skydome, the new stadium for the professional baseball team, the Toronto Blue Jays, was completed, a downtown location was selected that would allow it to easily access public transportation. The stadium, which seats 54,000 spectators, is linked by a pedway to Union Station, which provides both subway and GO Transit service. The stadium itself has only 500 parking spaces on site with the intention that parking from nearby office towers could be utilized during the evenings and weekends, which is when most of the Blue Jay’s games are played.

As an extension to zoning requirements, in 1991, the City of Toronto introduced a requirement for Environmental Service Plans of all new developments, which must include TDM plans for any new commercial development with more than 75 parking spaces. This too has served to reduce travel demand by an estimated 25 percent when such plans have been implemented ([9]).

Significant to maintaining liveability, Toronto has not built any new freeways in the central area since 1966, although several subway lines have been completed. This is in part due to very few corridors still existing which can be such developed. The freeway system within Toronto, however, is substantial, with Highway 401 through downtown Toronto expanding to 18 lanes in places, with an Annual Average Daily Traffic volume (AADT) in excess of 500,000 between Weston Road and Highway 400 ([16]). Toronto has, however, seen the construction of Highway 407 to the north of the central area. This road is built as a toll road and serves to bypass traffic from the core area of the city to the north.

Toronto has also sought to promote cycling. All major commercial developments are required to provide bicycle parking and shower and change facilities for cyclists. Toronto has also improved its cycle network. The result has been an increase of 75 percent in bicycle traffic between 1987 and 1993 ([9]).

Application

The next step is to analyze what Toronto has applied and see if it has application elsewhere. On this matter, Knight and Trygg note that significant development has occurred around many of the stations in Toronto, but that much of this is the result of a combined focus of “aggressive zoning, joint public/private development, and, in general, carefully coordinated transit and land-use development” ([17]). This should provide encouragement to those jurisdictions that are contemplating transit based decisions in land-use planning, but should serve as a warning against half-hearted efforts.

In general, regarding TDM plans, Apogee Research has noted that:

“…attempts to change or reduce travel [must be made] by changing fundamental conditions influencing travel — how often one must go to work or the distances between dwelling places, work places, and other destinations — not by trying to change travel under existing conditions. As such, they require more fundamental changes in people’s life styles than merely changing from one vehicle to another.” ([18], p. 45)

As a general principal, Kaufmann and Jemelin note that:

“Numerous studies have demonstrated the correlation between available public transportation, the road network (infrastructure and parking facilities) and the location of the activities of residents in urban areas (Kaufmann 2000, Pharoah & Apel 1995, Wegener and Fürst 1999). The obvious conclusion is that any attempt to encourage modal split must take these three factors into account. Notably, an attempt to change transport alone by increasing the available public transportation, carefully allocating the use of city roads and controlling parking facilities is ineffectual if the city is being built around road networks located on the outskirts.” ([19], p. 295)

Thus, in attempting to repeat the success Toronto has found elsewhere, it should be remembered that Toronto’s efforts are the results of many years of dedication to the goal of a multimodal transportation system and a liveable city, and that the efforts have been made have included more than just transportation policy or land-use policy in isolation.

Conclusions

Toronto has achieved a unique situation in North America — it is a major city that has maintained a dense core of population and employment and a well-functioning public transit system, and thus is one of the most liveable cities on the continent. This has been accomplished through years of deliberate decisions to integrate land-use and transportation planning with policies such as limiting freeway construction, zoning regulations and parking controls, and promoting transit and bicycle use. There is nothing unique about Toronto that keeps these lessons from being applied elsewhere, but it has been noted the need for both long term vision and dedication to that vision are required to bring it to fruition.

Epilogue

After I completed this paper, I came across The Big Move. The Big Move exemplifies what has made public transportation work in Toronto for all these years — it covers the region (now Greater Toronto all the way out to Hamilton), has committed funding from the provincial government, and has reasonable but daring goals. The plan makes it exciting to see what will evolve in the public transit sphere for the next 20 years in Toronto and area.

References

[1]. Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census divisions, 2006 and 2001 census — 100% data. Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/popdwell/Table.cfm?T=702&PR=35&S=0&O=A&RPP=25. Accessed November 5, 2009.

[2]. Wikipedia contributors. Toronto. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Toronto&oldid=313541166 Accessed September 13, 2009.

[3]. Wikipedia contributors. Toronto Transit Commission. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Toronto_Transit_Commission&oldid=324164672 Accessed November 6, 2009.

[4]. Wikipedia contributors. Toronto ON Toronto Skyline2 modified. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Toronto_ON_Toronto_Skyline2_modified.jpg Accessed November 14, 2009.

[5]. Filion, P. Rapture or Continuity? Modern and Postmodern Planning in Toronto. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. Vol. 23, Issue 3, 2002, pp. 421-444.

[6]. Newman, P.W.G. and J. R. Kenworthy. The Land Use-Transportation Connection. Land Use Policy. Vol. 13, No. 1, 1996, pp. 1-22.

[7]. Wikipedia contributors. Spadina Expressway. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Spadina_Expressway&oldid=314667890 Accessed November 6, 2009.

[8]. City of Toronto Achieves, This month in Toronto’s History. City of Toronto. http://www.toronto.ca/archives/thismonth.htm. Accessed December 1, 2009.

[9]. Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of American Cities. Random House Publishing, 1961.

[10]. Stewart, G. and R. Pringle. Toronto’s tentative approach to TDM. Energy Policy. Vol. 25, Nos 14-15, 1997, pp. 1203-1212.

[11]. Newman, P. and J. Kenworthy. Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence. Island Press. 1999.

[12]. Filion, P. and K. McSpurren. Smart Growth and Development Reality: The Difficult Co-ordination of Land Use and Transport Objectives. Urban Studies. Vol. 44, No. 3, 2007, pp. 501-523.

[13]. Kenworthy, K. R. and F. B. Laube. Automobile Dependence in Cities: An international Comparison of Urban Transportation and Land Use Patterns with Implications for Sustainability. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. Vol. 16, Issues 4-6, 1996, pp. 279-308.

[14]. Frank, L.D., and G. Pivo. Impacts of mixed use and density on utilization of three modes of travel: single-occupant vehicle. Transit, and walking. Transportation Research Record. No. 1466, 1994, pp. 44-52.

[15]. Nowlan, D. M. and G. Stewat. Downtown Population Growth and Commuting Trips: Recent Experience in Toronto. Journal of the American Planning Association. Vol. 57, Issue 2, 1991, pp. 165-182.

[16]. Wikipedia contributors. Highway 401 (Ontario). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Highway_401_(Ontario)&oldid=325649977 Accessed November 16, 2009.

[17]. Knight, R. L., and L. L. Trygg. Land-use impacts of rapid transit systems: implications of recent experience. US Department of Transportation, 1977.

[18]. Apogee Research. Costs and Effectiveness of Transportation Central Measures (TCMs) : A Review and Analysis of the Literature. US National Association of Regional Councils, 1994.

[19]. Kaufmann, V. and C. Jemelin. Coordination of land-use planning and transportation: how much room to maneuvers? International Social Science Journal. Vol. 55, No. 2, 2003, pp. 295-305.

Comments

Fascinating article. Interesting statistics and helps to explain why I believe and also tell people whenever I travel to other countries that Toronto is a very livable city.

Chris Myers