Abstract

Public transit has existed in China since 1969 with the opening of the Beijing Metro. Today, Shanghai has the largest metro system in the world, and is one of ten mainland Chinese cities, in addition to Hong Kong, that have a metro system. In addition, there are thirty more cities in China with metro systems either under construction or in planning stages.

The Hong Kong opened its metro system in 1979 in an effort to reduce traffic congestion. Today, public transit on the whole is very popular, with over 80% mode capture rate. Hong Kong continues to expand its rail transit network, but at a slower rate than many cities in mainland China. The system operator has also taken on the role of developer, generating more profits from property management than railway fares, and in the process has provided a very successful example of Transportation Oriented Development (TOD) policies in action, which are a model for TOD efforts worldwide.

In summary, a short compare and contrast between China’s fast growing cities of today and post-World War II American cities is provided. Both are growing (or grew) at incredible speeds, have rising middle classes and significant economic growth. What Chinese planners can note is that in America, highways were chosen over public transportation options. Today, that means that traffic congestions remains a major problem in many American cities. Additionally, funds to maintain infrastructure have waned as the cities’ growth has slowed with the slowing of economic growth.

Introduction

Public transit is a relatively new phenomena in China. Planning for the Beijing Metro began with the help of Soviet experts in 1950, but it would be almost twenty years until the system would open with one line in 1969. In the next twenty-five years, only Tianjin would open a metro system. However, starting with Shanghai in 1995, a significant number of Chinese cities have opened metro systems and expanded their existing systems. Today, Shanghai has the largest system in the world; there are ten cities with systems in operation and 30 more with systems under construction or in planning. However, there are over 100 Chinese cities with a population greater than 1 million, generally considered to be the breakpoint where metro systems become feasible (1). While urban rail transport is starting to gain traction in China, there is still much possible expansion.

Hong Kong, as a former British colony, has a much different history in urban public rail. The first line opened in 1979 as an effort to reduce traffic congestion. From the beginning, the rail system has been very successful, as demonstrated by the fact that over 80% of Hongkongers use public transportation for their trips.

A brief history of select metro systems in mainland China, along with the history of the metro in Hong Kong, is presented. Following that, some observations based on the comparison of the development path Chinese cities are undertaking today is compared to the development path pursued by American cities following World War II.

A History of Public Transit in Mainland China

Current mode split in Chinese cities, as noted in Table 1, shows that public transit (all forms) currently has a mode capture of 19%. This share has likely increased over the last ten years as there has been significant construction of urban rail systems in the intervening time. In 2002, in addition to Hong Kong, there were four cities in mainland China with operating metro systems: Beijing (opening in 1969), Shanghai (opened in 1995), Guangzhou (opened in 1997), and Tianjin (opened in 1984) and systems in Shenzhen, Nanjing, Chongqing, and Wuhan were under construction (2). Today there are 10 cities with metro systems in operation (Dalian and Shenyang, in addition to the above noted cities). Many of China’s large cities had laid out ambitious metro construction plans, however, in 1995, China’s State Council suspended most applications for construction, beyond those for Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Beijing. There were two major concerns: a low number of passengers and high construction and maintenance costs. The former is due in part a lack of an integrated public transit fare system and the latter due to varied technical specifications and the need to import nearly all construction equipment and rolling stock. To combat the latter, when the moratorium on metro construction was lifted in May 1999 by the Chinese State Council, it came with the condition that new systems must have a domestic content of 60% or better (2). Further refined in September 2003, the General Office of State Council stated that only cities with a population over 3 million, an annual budget of at least $1.5 billion and GDP of over $15 billion would be approved for subway lines with a one-way capacity over 30,000 people/hour and only cities with a population over 1.5 million, a annual budget of at least $850 million and a GDP of over $8.5 billion would be approved for light rail projects with a one-way capacity over 10,000 people/hour (1).

| Mode | Mode Capture |

|---|---|

| Walking/Cycling | 65% |

| Transit | 19% |

| Private Motor Vehicle | 16% |

It is worth noting that, by annual ridership, the Beijing (#5), Hong Kong (#8), and Shanghai (#9) systems are in the top ten systems worldwide. Guangzhou is ranked #15 (3). Recent reports suggest that Shanghai currently has more passengers than Beijing (1). The four biggest players in mainland China remain Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen (market share for 2010 noted in Table 2, which together account for 64% of Chinese urban rail passengers (1)).

| Major Player Market Share | Range |

|---|---|

| Shanghai Shentong Metro Group | 28% |

| Beijing Subway Operation Co., Ltd. | 18% |

| Guangzhou Metro Corporation | 11% |

| Shenzhen Metro Co., Ltd. | 7% |

| Other | 36% |

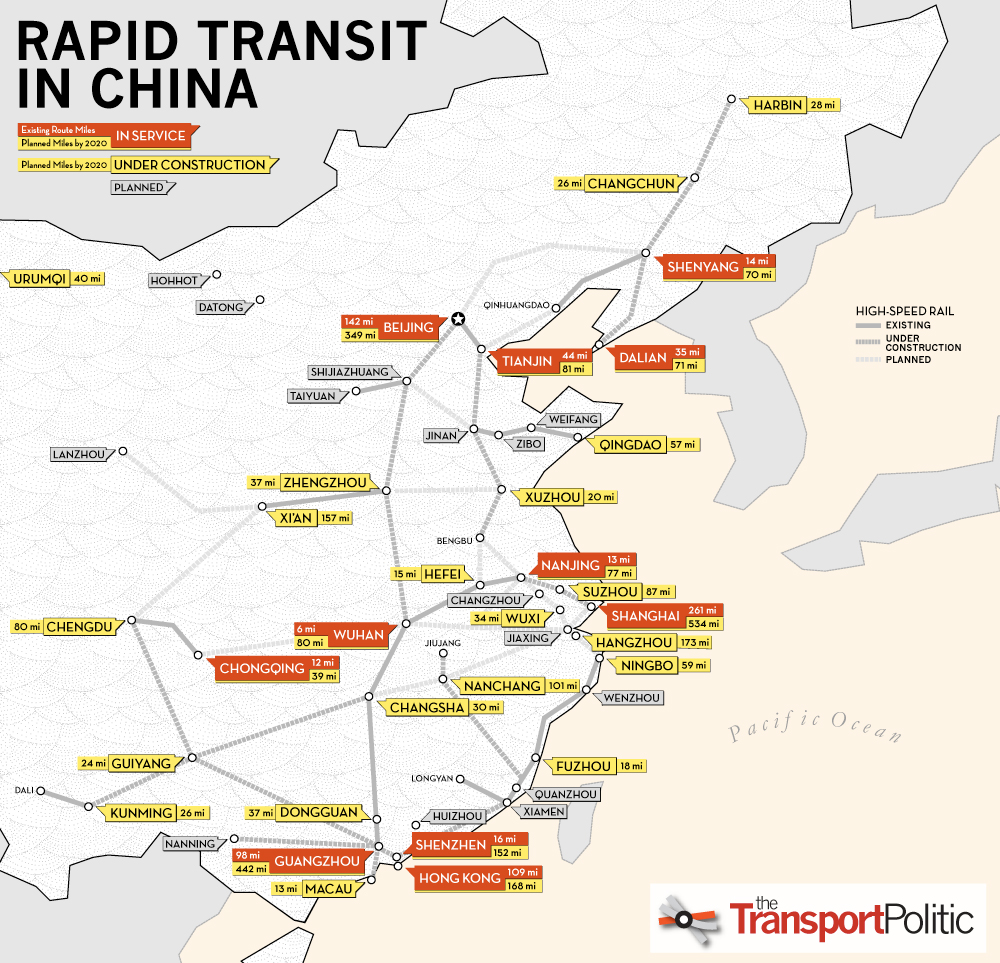

Today, there are over 100 cities in China with a population of over 1 million but only ten cities have either subway (metro) or light rail systems in operation while thirty have rail transit projects in either the planning or preparatory work stage, meaning that the potential explanation of rail transit in China is huge. Today, the four biggest players remain Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen (market share for 2010 noted in Table 2), which together account for 64% of Chinese urban rail passengers (1). Probably in light of the fact that 50% of the country’s population is expected to be urban by 2020 and 75% by 2050, major expansion of urban rapid transit has begun in China. The Chinese central government has committed to spending USD $1 trillion by 2015 on grade-separated urban transportation corridors. This is expected to increase the length of urban rail from the 600 miles (975 km) today to 1,900 miles (3,075 km) in five years. The image below provides an overview of the cities that will see this investment (4) (click on the image to see an enlarged version).

Rapid Transit in China, Today and 2020 (4)

Beijing

Beijing Metro Logo

The Beijing Metro was the country’s first, originally planned with the help of Soviet experts and the concept originally unveiled in 1953. Chinese planners took particular interest in the use of the Moscow Metro during the Battle of Moscow during World War II, and so the Beijing Metro was designed from the very beginning to serve both civilian and military ends. Increasing tensions between the Soviet Union and China led to Soviet experts slowly being withdrawn in 1960 and completely removed by 1963. Determined to press ahead, the metro opened in 1969 to mark the 20^th^ anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (5). The original system was designed with the ability to transport 5 to 6 divisions from Xishan to Beijing in the case of a Soviet invasion. To this day there remains two stations at Xishan that are reserved for military use and not open to the public (6).

The system was opened to the general public in 1977 and to foreign visitors in 1980 (6). For many years, the expansion of the system was slow or non-existent. Winning the Olympic bid in 2001 for the 2008 Summer Games provided a catalyst for investment, resulting in seven more lines opening, bringing the total to nine. Today (2010), there are nine lines open (Line 1, Line 2, Line 4, Line 5, Line 10, the Olympic Branch Line (Line 8, Phase I), Line Batong, and the Airport Express line) representing 147 stations and 228 km of track (5). Line 4 is the last of these to open in September 2009 and represents a joint venture with the Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway (MTR). MTR owns a 49% stake in the project, was required to provide 30% of the capital, and will receive a concession to run the line for 30 years (7).

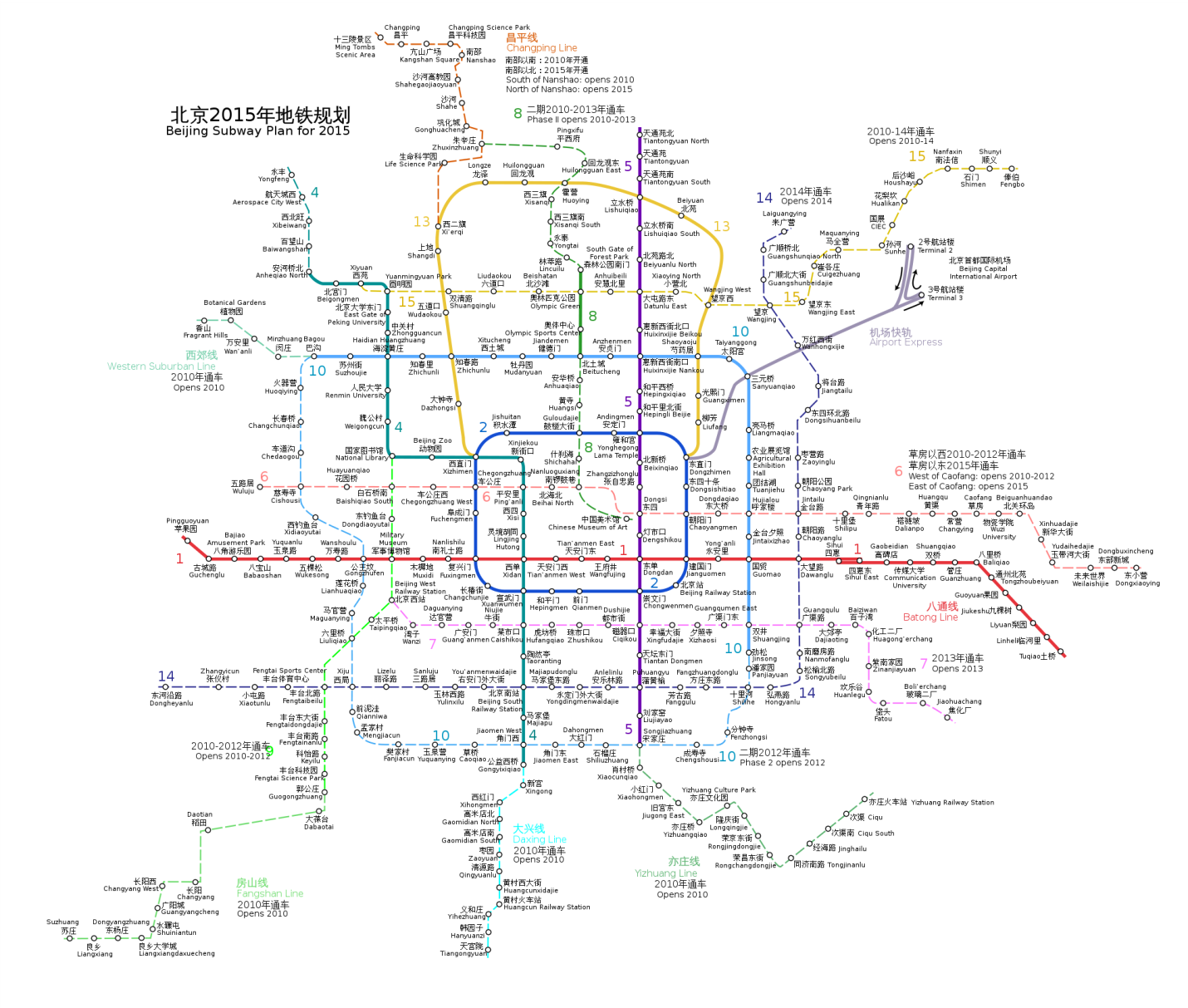

The Chinese Central Government has made continued investment in urban public rail a priority, in part to try to relive pressure created by increasing urban populations and car ownership. There are currently 10 additional lines under construction in Beijing, with the construction of two more expected to begin this year. This will bring the system length to 420 km by 2012 and to 561 km by 2020 (8). Below is a diagram of the proposed system to be in place by 2020 (not 2015, as noted in the diagram).

Beijing Subway Plan for 2020 (9)

Tianjin

Tainjin Metro Logo

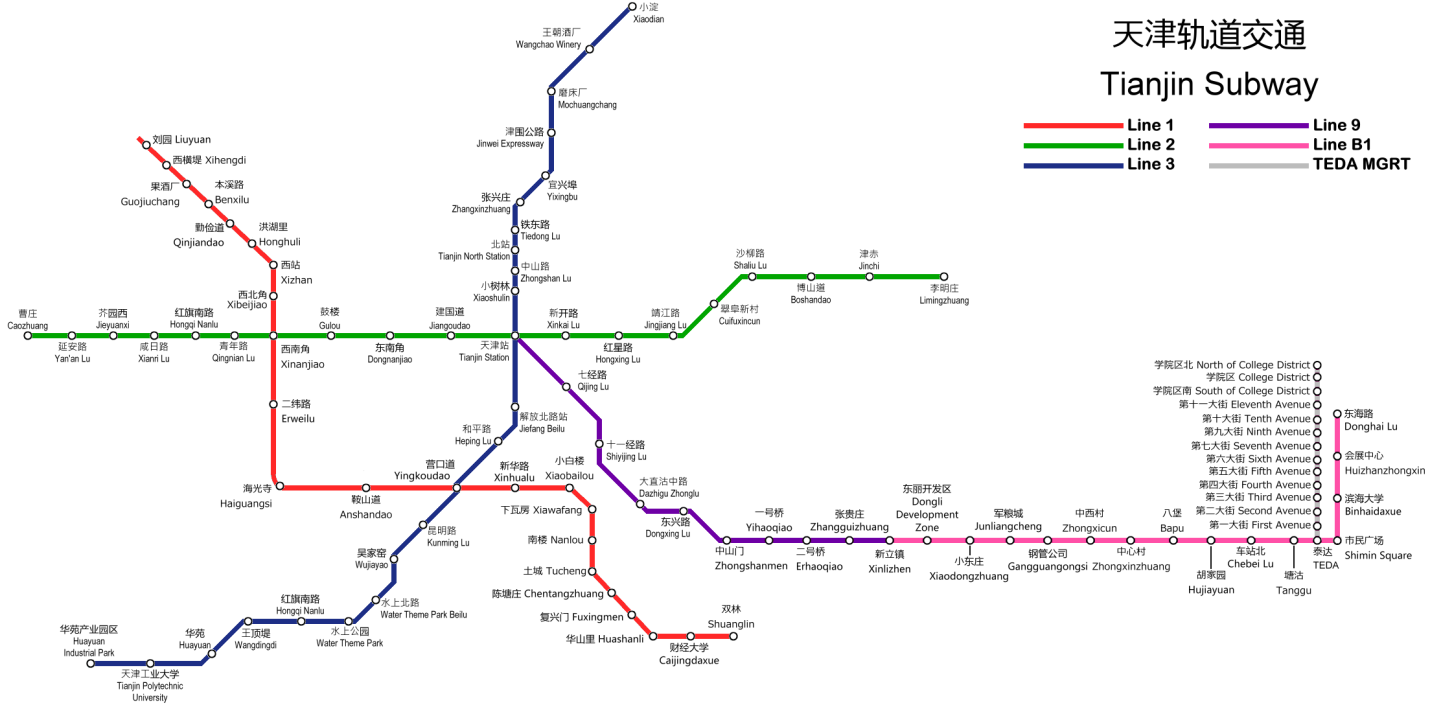

The Tianjin Metro was the second to open in China, opening the first few stations in 1976 and the first line being completed eight years later in 1984. The impetus had been the increasing number of motor vehicles, particularly trucks, in the 1950’s, which was causing the existing surface tram system to cease working effectively. Much of the system was constructed in a former canal. The system was slowly expanded during the 1970’s and 80’s, but by the end of the 1990’s, the systems was very much out of date, and so closed in September 2001 for renovations and reopened five years later in December of 2006. Today, there are 22 stations on three lines (Line 1, Line 9 and the TEDA MGRT) and 26 km of track. Lines 2 (opening 2011), 3 (opening 2012), 5 (opening 2013), and 6 (opening 2013) are currently under construction, and Lines 4, 7, and 8 remain in the planning stages (10). Below is a map of the Tianjin Metro system.

Tianjin Subway, Including Lines Under Construction (11)

Shanghai

Shanghai has a rich history, rising to particular importance following the Opium Wars (1839-42), after which it was opened to foreign trade. In the years that followed until World War II, Shanghai rose to become a global financial center. In the wake of the Communist victory of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 brought closure of Shanghai to much of the rest of the world, but the economic liberations of the 1980’s and 90’s brought redevelopment and eventually foreign investment. In 2005, Shanghai became the world’s largest port (12). Today, Shanghai is well on its way to reclaiming its spot as an important world city.

Shanghai Metro Logo

The first line of the Shanghai Metro opened in 1995 as a north-south axis from the Central Station to the southern suburbs. In recent years, the metro system in Shanghai has undergone a significant expansion and is now the world’s largest system. In 2007, the system was comprised of over 250 km of track and moved 814 million passengers annually. By comparison, in 2000, the system has only 63 km of track and moved only 136 million passengers annually. This corresponds to a mode capture of 5% in 2000 and 22% in 2007 (1). The World Expo, being held May 1 to October 31, 2010, has lead to a significant investment in Shanghai’s metro system, with six lines either built or significantly expanded in preparation. Today there is over 420 km of track on 12 lines with 268 stations, in addition to a short maglev line that runs from the airport. By 2020, it is anticipated that there will be 22 lines in operation with 877 km of track (see below) (13).

Shanghai Metro Map (14)

Shanghai’s metro system is unique in China in that it runs on 1,500V DC power and is powered via overhead cantery, in part because of the high voltage (most metro systems run on 750 V DC and are powered via a third rail) (15).

Guangzhou

With a history stretching back more than 2100 years, Guangzhou has a varied and rich history. Established during the Qin dynasty as a provincial capital in AD 214, Guangzhou is known for its shipbuilding industry and its port over the centuries. Indeed, in the years leading up to the Opium Wars (1839-42) it was the only port open to the West. Guangzhou has struggled in modern times as, for various reasons, the port was closed to the outside world. Starting with China’s economic reforms in the last 1970’s and its designation in 1984 as an ‘open city’, Guangzhou has sought to reclaim its past glory and importance. Guangzhou, at the center of the Pearl River Delta, faces tough competition in this regard from both Hong Kong and Shenzhen. Metro construction is one part of a plan launched in 1997 to restore the city image and remake it into a regional hub for southeast China and Southeast Asia (16).

Guangzhou Metro Logo

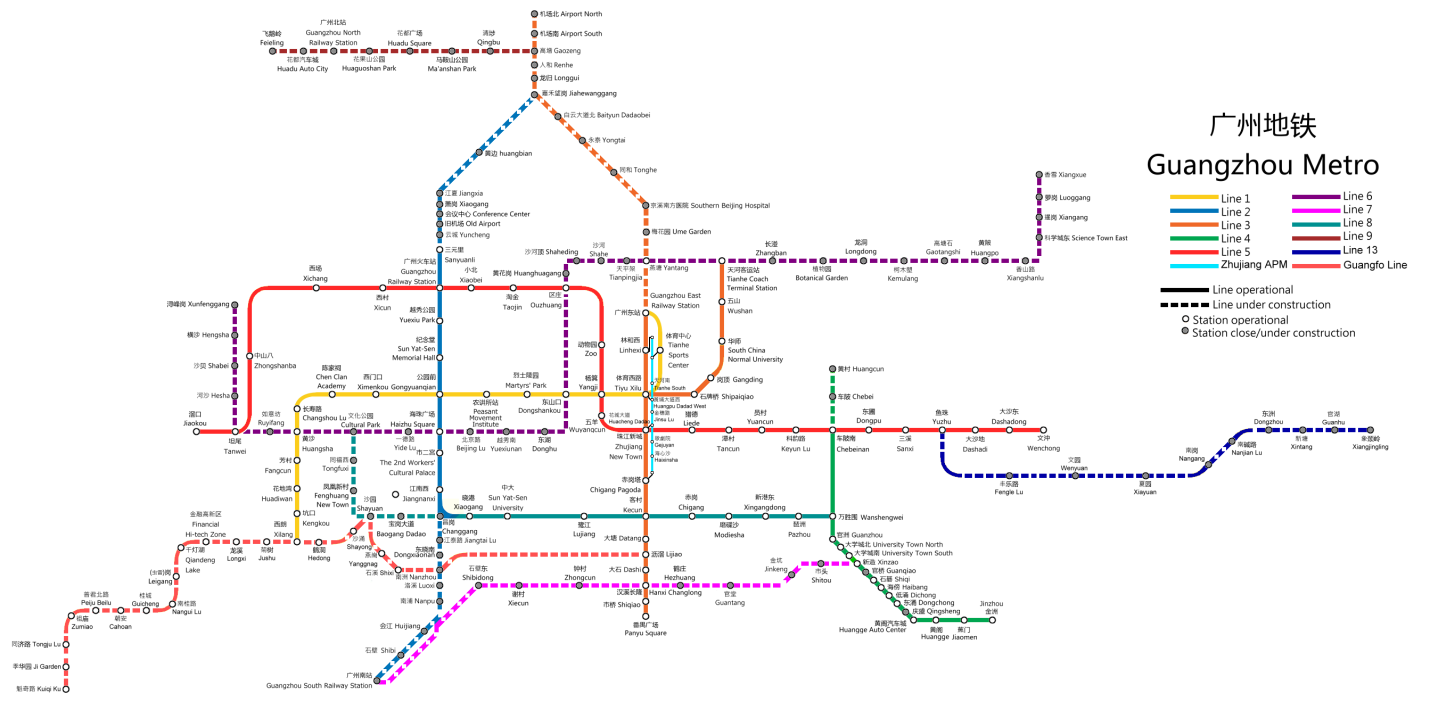

The construction of the Metro in Guangzhou began in December 1993 and the first line was completed in June 1999. It was a turnkey project, led by Siemens, with 16 stations and a total track length of 18.5 km (17). Metro Line 2 began construction the same year and entered service in June of 2003 (18). Currently there are five lines open with 80 stations and over 150 km of track. There are three lines under construction with four more in planning stages. The system is expected to grow to 191 km by 2010 (see below for 2013 system) and over 600 km in the long term.

Guangzhou Metro Map (2013) (19)

Shenzhen

Before 1979, Shenzhen was a sleepy fishing village with a population of 300,000. That year brought Shenzhen the designation as the first of China’s Special Economic Zones, in part to serve as a buffer between Hong Kong and mainland China. Today, it has a population of 14 million and in 2009 was ranked as the number five financial center in the world after London, New York, Hong Kong, and Singapore (20).

Shenzhen Metro Logo

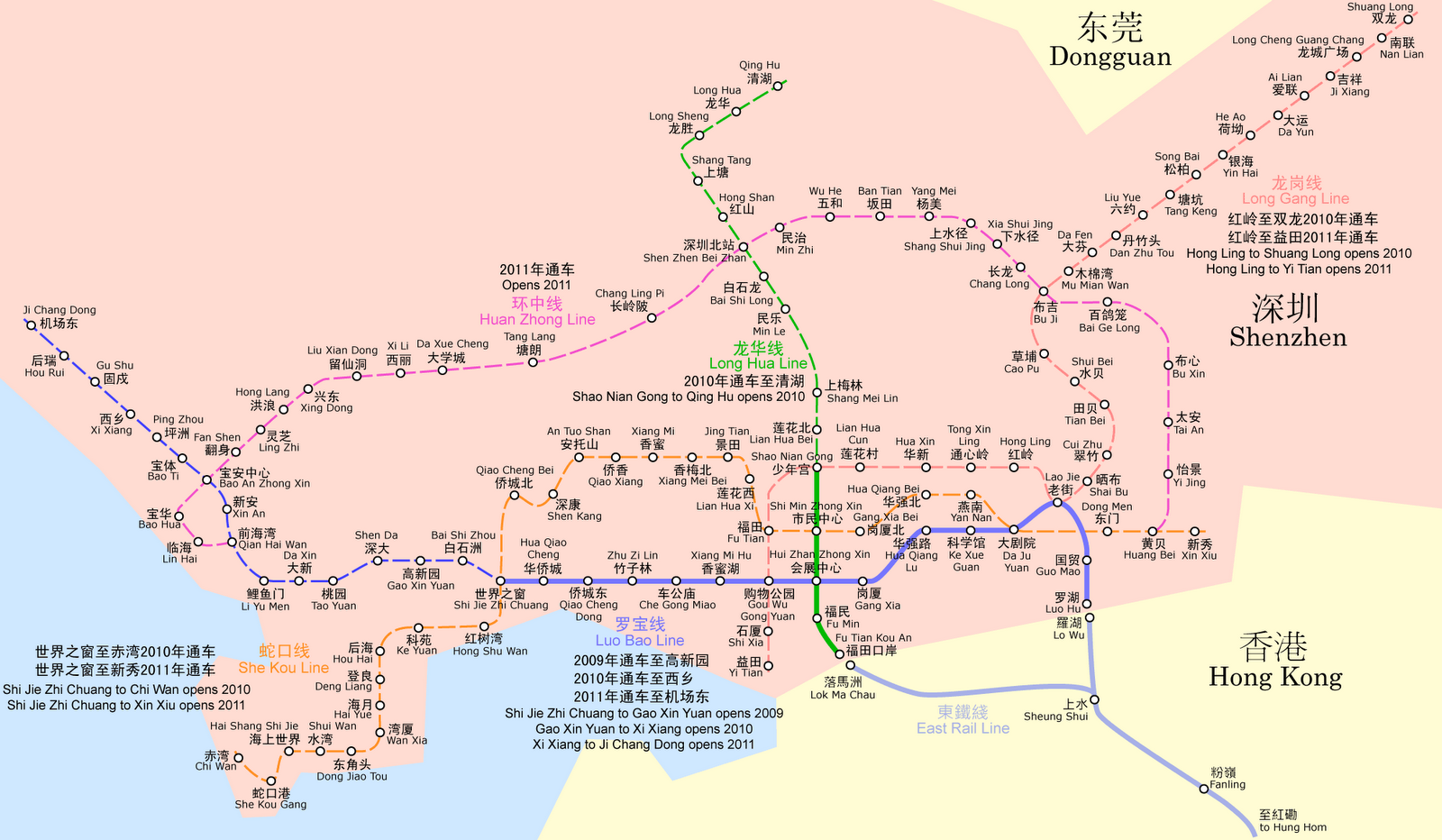

The Shenzhen Metro opened in December 2004, the fifth city in mainland China to open a metro. The metro system currently has 2 lines with 22 stations and 25 km of track in use. It is anticipated that there will be 177 km of track in service by 2011 (see below) (21). Plans of the expanded 2020 system can also be found below.

Shenzhen Metro Map (22)

Shenzhen Metro Network in 2020 (23)

Due to its location near Hong Kong, part of the expansion to be complete in 2011 will be a reciprocal agreement allowing a unified system of fare payment for both the Hong Kong and Shenzhen Metro Systems (21).

Hong Kong

MTR Logo

Hong Kong was a British colony until 1997 when it was handed back to China, but has continued to maintain a political and economic system much different than that found in mainland China. As such, the history of Hong Kong’s metro system is much different than systems in mainland China. The Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway (MTR) opened in 1979 as a result of a 1967 government study began as an effort to ease the territory’s growing traffic problem. In 2006, a merger of the operations of MTR and the Kowloon-Canton Railway Company (KCR) (providing rail service to the New Territories and Guangzhou and light rail in the New Territories) was effectuated, with merger of payment systems competed in December 2007. Today, the combined MTR network includes 212 km of rail with 150 stations (24) and is the most commonly used transportation option in Hong Kong, capturing 42% of the public transportation market (25). Hong Kong has a highly developed public transportation systems which has a mode capture rate of more than 80%, one of the highest rates in the world (26). Hong Kong’s Metro system is undergoing an expansion, although much smaller than many mainland Chinese cities (a map of the expanded network can be found in below), due, no doubt in part, to the already extensive nature of the system.

Future MTR Network (27)

Success with Transportation-Oriented Development in Hong Kong

MTR has branched beyond solely providing public transit and has become a major land developer in Hong Kong, often developing the immediate area of new stations. In fact, in 2009, MTR made more profit from property management (HK$3.55 billion) than from transport operations (HK$2.12 billion) (25).

Much of the success of MTR is believed to relate to the high density of both workers and population near MTR stations with over 20% of housing units lying within 200 m of an MTR station, and over 43% within 500 m. This means that some 2.78 million people live within 500 m of a station. Each public housing unit within 500 m of an MTR stations accounts for 1.97 passengers per day and each private housing unit accounts for 1.62 passengers per day. Mixed land use surrounding stations, as well as high densities, are highlighted as part of the success of MTR. MTR also, in its developments, aims to minimize ‘unnecessary transportation’ by avoid deliberately place facilities (such as schools or shops) beyond walking distance, where possible (28).

Moving Forward

Growth of megacities and regions means that to fully understand the urban transportation picture, intercity rail links must be considered, especially in light of China’s High Speed Rail (HSR) push. HSR has the possibility of expanding the effective area of a metropolitan to a radius of 200 km or more, as demonstrated by Paris and others.

Because of the pace at which China is building, finding up-to-date and accurate information is nearly impossible. There are many forecasts for the 2010 systems made 2-5 years ago, but it is hard to confirm what has opened and what is still under construction, and what never made it off the drawing board (e.g. the Maglev expansion to the Expo 2010 site in Shanghai). Current plans typically provide current system data and plans up to 2012, which seems to be the end of the current building cycle. What will happen after is anyone’s guess.

The current building spree has been launched and accelerated by the stimulus package from the Chinese central government, a common response to the current economic climate by many governments worldwide, however China has typically spent enormous amounts of money — by some estimates, 10% of their GDP — each year on infrastructure, even in ‘normal’ years. This pace has meant that Wikipedia and public transportation blogs, particularly The Transport Politic, are vital to understanding the current situation in China, due to their ability to be updated as events unfold, rather than the 6-12 month publishing cycle typical of peer-reviewed papers. In fact, between drafts of this paper, the Transport Politic published a summary (4) of the state of public rail transit in China that radically changed the conclusions of this paper.

For now, Chinese cities have continued to grow at phenomenal rates, due almost exclusively from in migration (as opposed to natural growth). This, combined with the rapid growth in the Chinese economy, has made it easy to support ambitious infrastructure projects. However, the Chinese would do well to remember the lessons that have been learnt in the United States. The US once had compact cities, including ‘streetcar suburbs.’ In the years following World War II, American cities blossomed, with a rising population (mostly due to natural growth in this case), an expanding economy, and an expanding middle class. Against this backdrop, American cities became increasingly fordist, separating land uses into separate zones which increased travel demand, and which, because of distance, was typically filled by the use of private motor vehicles. Today, much of that momentum has waned, leaving grand projects such as the Eisenhower Interstate System of yesteryear and any proposed national HSR network to languish in political no-man’s land. While the debate continues, existing urban and transportation infrastructure becomes increasingly fragile as infrastructure maintenance funding is diverted to more politically ‘sexy’ programs and much of the existing infrastructure built in the 1950’s and ‘60’s nears the end of its 50-75 estimated lifespan.

China, with cities whose population is often a magnitude of order larger than their American counterparts in 1950, has already started to run into the traffic congestion problems and space constraints for transportation infrastructure that took much longer to develop in America. In cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, public transit is seen, at least in part, as an answer. Chinese cities, as they develop and redevelop, would to do well to remember the guiding principal of reducing the need for trips to begin with, which has worked exceptionally well for Hong Kong’s MTR in particular, and Hong Kong as a whole.

Conclusion

Public transit is an area of high growth in China. As an example, Shanghai went from lacking an operational metro system before 1995 to having the world’s largest system today in 2010. The sheer size of the Chinese population has meant that expansions to existing systems, as well as metro systems in new cities, are often at capacity soon upon completion. This is typical of Chinese cities, although the scale of Shanghai (population of 19 million) has made the rise of its metro system particularly remarkable. In short, at the present time, Chinese cities, including their public transit systems, are in a growth phase.

The caution is given to Chinese planners to consider long-term implications of their transportation network choices and to learn from international experience. Hong Kong has seen much success in reducing private automobile use through the use of urban public rail and so can be considered an example both to Chinese cities and the rest of the world. American cities, by contrast, choose to expand their highway systems during a period of strong growth following World War II and today have a transportation system that is nearly its limits, both in terms of capacity and life cycle. Chinese cities, and growing cities worldwide, do well to consider the long term impact of their transportation network choices of today.

References

1. IBISWorld. IBISWorld and ACMR China Industry Report: Underground Rail and Subway Transportation in China: 5320. 2010.

2. Kenworthy, J., and F.B. Laube. The Millennium Cities Database for Sustainable Transport. Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

3. Wikipedia contributors. Metro systems by annual passenger rides. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, May 9, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Metro_systems_by_annual_passenger_rides&oldid=361069182. Accessed May 13, 2010.

4. Freemark, Y. China Expands Its Investment in Rapid Transit, Paving Way for Future Urban Growth. The Transport Politic, May 13, 2010. http://www.thetransportpolitic.com/2010/05/13/china-expands-its-investment-in-rapid-transit-paving-way-for-future-urban-growth/. Accessed May 13, 2010.

5. Wikipedia contributors. Beijing Subway. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, May 13, 2010. <http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Beijing_Subway&oldid=361885456. Accessed May 13, 2010.

6. citw2008.com. Touring Beijing: The Beijing subway’s History. Beijing International Travel Website, 2006. http://china.citw2008.com/html/2006/1106/1123.shtml. Accessed May 13, 2010.

7. MTR Corporation Limited. Beijing Metro Line 4. Projects in Progress (China), 2009. http://www.mtr.com.hk/eng/projects/china_beijing.html. Accessed May 13, 2010.

8. People’s Daily. Beijing to build world’s longest metro. People’s Daily Online, Nov 10, 2008. http://english.people.com.cn/200611/20/eng20061120_323289.html. Accessed May 13, 2010.

9. Ran. Beijing-Subway-Map.svg. Wikipedia Commons, March 7, 2009. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beijing-Subway-Plan.svg. Accessed May 13, 2010.

10. Wikipedia contributors. Tianjin Metro. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, May 5, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tianjin_Metro. Accessed May 13, 2010.

11. ASDFGH. File:Tianjin Subway map (under construction).jpg. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, January 28, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tianjin_Subway_map_(under_construction).jpg. Accessed May 13, 2010.

12. Wikipedia contributors. Shanghai. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, May 14, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shanghai&oldid=362129050. Accessed May 16, 2010.

13. Wikipedia contributors. Shanghai Metro. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, May 11, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shanghai_Metro&oldid=361496429. Accessed May 16, 2010.

14. Freemark, Y. Shanghai’s Metro, Now World’s Longest, Continues to Grow Quickly as China Invests in Rapid Transit. The Transport Politic, April 15, 2010. http://www.thetransportpolitic.com/2010/04/15/shanghais-metro-now-worlds-longest-continues-to-grow-quickly-as-china-invests-in-rapid-transit/. Accessed May 15, 2010.

15. Schwandl, R. Shanghai Subway - Metro. UrbanRail.Net, 2004. http://www.urbanrail.net/as/shan/shanghai.htm. Accessed May 15, 2010.

16. Xu, J., and A. G.O. Yeh. City Profile: Guangzhou. Cities, Vol. 20, no. 5, 2003, pp. 361-374.

17. Schwandl, R. Guangzhou Metro. UrbanRail.Net, 2007. http://www.urbanrail.net/as/guan/guangzhou.htm. Accessed May 14, 2010.

18. Guangzhou Interactive Information Network Company. Planning Status for Guangzhou Metro Construction. Life of Guangzhou, Feb 16, 2006. http://www.lifeofguangzhou.com/node_10/node_38/node_61/2006/02/17/1140159583190.shtml. Accessed May 14, 2010.

19. ASDFGH. File:Guangzhou Metro MapB.png. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, January 25, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Guangzhou_Metro_MapB.png. Accessed May 14, 2010.

20. Eddsterone, Shaund, et al. Shenzhen travel guide. Wikitravel, May 11, 2010. http://wikitravel.org/en/Shenzhen. Accessed May 14, 2010.

21. Wikipedia contributors. Shenzhen Metro. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, May 12, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shenzhen_Metro&oldid=361686943. Accessed May 14, 2010.

22. Ran. File:Shenzhen-Metro-Plan.png. Wikipedia Commons, July 20, 2008. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shenzhen-Metro-Plan.png. Accessed May 14, 2010.

23. Andao. File:SZ Railway 2020 English.png. Wikipedia Commons, October 24, 2009. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SZ_Railway_2020_English.png. Accessed May 14, 2010.

24. Wikipedia contributors. MTR. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, May 3, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=MTR&oldid=359890615. Accessed May 6, 2010.

25. MTR Corporation. 2009 Interim Results. MTR > Investor’s Information, August 11, 2009. http://www.mtr.com.hk/eng/investrelation/annualresult2009/MTR_interim_2009_web.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2010.

26. Wang, L. H. In Search of a Sustainable Transport Development Strategy for Hong Kong. Hong Kong Policy Research Institute Ltd., http://www.hkpri.org.hk/bulletin/5/l-h-wang.html. Accessed May 12, 2010.

27. Xavier114fch. File:FutureMTRNetworkAfterMerger.png. Wikipedia Commons, Aug 14, 2009. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FutureMTRNetworkAfterMerger.png. Accessed May 17, 2010.

28. Tang, B.S., Y.H. Chiang, A.N. Baldwin, and C.W. Yeung. Study of the Integrate Rail-Propery Development Model. Hong Kong, 2004.

29. Wikipedia contributors. MTR Corporation. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, April 29, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=MTR_Corporation&oldid=358997078. Accessed May 6, 2010.

30. ASDFGH. File:Tianjin Metro Corporation logo.png. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, August 12, 2009. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tianjin_Metro_Corporation_logo.png. Accessed May 13, 2010.

31. Schwandl, R. TIANJIN (Tientsin) Subway. UrbanRail.Net, 2004. http://www.urbanrail.net/as/tian/tianjin.htm. Accessed May 13, 2010.

32. Ran. File:Shenzhen-Metro.png. Wikipedia Commons, Dec 13, 2009. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shenzhen-Metro.png. Accessed May 14, 2010.

33. Keithorz. File:SZ Railway 2011.png. Wikipedia Commons, May 14, 2008. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SZ_Railway_2011.png. Accessed May 14, 2010.

34. ASDFGH. File:Guangzhou Metro MapA.png. Wikipedia Commons, April 16, 2010. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guangzhou_Metro_MapA.png. Accessed May 14, 2010.

35. Joowwww. File:Shanghai Metro logo.svg. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, August 14, 2008. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shanghai_Metro_logo.svg. Accessed May 14, 2010.

36. ASDFGH. File:Beijing Subway logo.png. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, Oct 2, 2009. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Beijing_Subway_logo.png. Accessed May 13, 2010.

37. Tnds. File:Shanghaimetro Current.svg. Wikipedia Commons, April 22, 2010. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shanghaimetro_Current.svg. Accessed May 15, 2010.

38. Tnds. File:Shanghaimetro 2020.svg. Wikipedia Commons, April 10, 2010. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shanghaimetro_2020.svg. Accessed May 15, 2010.

39. Jackl. File:MTR Corporation.svg. Wikipedia Commons, Dec 11, 2007. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:MTR_Corporation.svg. Accessed May 17, 2010.

Comments

Excellent. I just wrote a post on my blog about my experience with the Shanghai Metro and came across your blog. Great work!

Hi, like your blog.

But your map of Chinese future high speed rail is out of date. Kunming is building high speed lines not only to Guiyang and Dali, but also to Nanning and Chengdu. Can you please edit your map to reflect this? Thanks!

Hey Matthew. There is an updated version of the map at Transport Politic (about halfway down).